Rubbish Brass: Rubbish Results?

Case quality and the pursuit of seeking to improve case consistency through sorting and preparation has long interested me – not just the mechanics but, the much trickier question of how much difference, if any, does after-purchase work i.e ‘prepping’, make. Best practice is to buy the highest quality cases you can find / afford, then only if necessary and/or appropriate undertake work (which may include neck-turning) to make them ‘better’.

In this context, I’d define ‘highest quality’ as being those makes with the reputation for making the most consistent and concentric products but, many handloaders see the purchase choice as being entirely how about many firings they expect from their cases balanced against initial cost. (For them ‘good’ often means thick-walled and heavy).

On the matter of post-purchase work or ‘prepping’, I’ve italicised the words ‘necessary’ and ‘appropriate’, as in many situations top quality cases are more than suitable straight out of the box, only needing mouth chamfering and running the necks over an expander mandrel to ensure consistent neck-tension. Serious post-purchase work is sometimes necessary. For instance, tight-neck chambers and/or reforming cases to a different form/calibre where neck-thickness reduction is essential for safe rifle operation – or even being able to physically chamber the cartridge. That can be both separate from or complementary to enhancing precision and is different from ‘clean-up’ or ‘trueing’ neck-turns which remove the minimum amount of metal to create a common, uniform neck thickness value for every case in the ammunition box. The first is mandatory; the second, optional.

In this context ‘better’ is partly about helping make each case as close to identical to its fellows as is feasible; also improving on its inherent ‘out of the box’ concentricity – in simple terms how straight the bullet lies in relation to the case-body and rifle-bore centrelines and, how square its alignment is to the case-head and bolt-face. Ninety plus percent plus of both elements (consistency and concentricity) comes from how well the case is made in the first place and, whilst the best out there from companies like Lapua, Norma and Peterson is very, very good indeed these days, cheaper products have generally improved over their counterparts of not too many years ago. We also have new entrants in this lower price market segment, principally Starline, whose products offer good value and appear to be well made.

Neck-turning and other case-conditioning activities are now supported by tools capable of producing precisely determined and very consistent results in capable hands. Whilst once minority activities, they’ve become widespread – just look at the growth in case-annealing – often with pricey, sophisticated chip-controlled electrical induction devices. The major handloading tools suppliers offer the less specialist tools these days, often in multi-use sets.

Handloaders have bought into the narrative that such work always generates precision improvements but, obtaining significant, or even any, improvement requires closely-dimensioned high-quality barrels and chambers in addition to good brass. Good rifle optics too – you need to see the target clearly to aim precisely and consistently. As a result, it is impossible to generalise on how much benefit case ‘prepping’ work produces in terms of results. (It is possible to produce worse results than doing nothing in some situations). In some applications, such as the 6PPC in short-distance benchrest competition, the consistently small groups that competitors produce speak for themselves. At the other extreme, don’t expect much, more likely anything at all, from spending hours on ‘prepping’ 243 Win cases for an old Brno, Parker-Hale or BSA deer rifle even if it is in excellent condition and seen little use.

Recycled

However, my topic for today isn’t about choosing top quality match brass then spending time weighing and measuring it, neck-turning it, or whatever – quite the reverse. It’s a look at loading up recycled once-fired 5.56 NATO arsenal cases from mixed origins for my 223 Rem F-Class rifle. ‘My God!’, I hear people say, ‘He’s lost it!’ To be honest, this hardly conforms to my earlier statement about buying the highest quality brass you can find/afford as best (in fact standard) practice.

Some background to this behaviour. Two things directed me down this path. The first occurred many years ago when I’d shoot lever and rimfire rifles on Friday mornings on a range created from worked-out sand quarries. During one range-session with a fellow club member, inside a hole in the ground, the adjacent but invisible, range was being used by a police firearms team, a regular weekday occurrence usually involving pistols, but something with a sharper bark was being fired that morning, 5.56mm assault rifle lookalikes.

When the racket finished, my shooting partner asked me to keep an eye on his gear and walked off, to return clutching a bag of fired cases having blagged them off the boys in blue. Being curious, I asked if I could have a look and found several hundred Winchester 223 Rem. cases. Genuinely once-fired of course, but I was appalled at the idea of reusing them given their banged-up condition – body dents, mashed necks, severely battered case-heads and rims from violent extraction and contact with ejector pegs. No doubt the rifle chambers were ‘generous’ too, hence fired brass dimensions needing heavy sizing before use. ‘Are you seriously considering reusing these?’ I asked, my view being they were only fit for scrap. The reply was in the affirmative but not by himself, as they were passed to his brother who was a gamekeeper on a Scottish sporting estate and used a 223 for predator culling. I was told that the recipient junked the worst damaged examples, reloaded the rest and obtained entirely satisfactory results over the distances shots were taken. Cases were lost in the estate’s thick ground cover, which allied to attrition from wear and tear left him perennially short of this expensive commodity. This made me think a bit about the very different imperatives and standards across rifle users of whom only a minority participate in precision orientated competition disciplines or long-range ‘varminting’.

‘Top Brass’

The more direct incentive occurred years later when I met Edgar Brothers’ then Sales & Marketing Director on Diggle Ranges one day. I was presented with a freebie in the form of 50 each refurbished 5.56 and 7.62 once-fired arsenal cases from an American outfit called ‘Top Brass’, packaged in 50-count bubble packs for rack display. A quick ‘Google’ shows that the company is still in business and 100 reconditioned 5.56 is priced at $26 before taxes and shipping, with packs of up to 1,000 cases available. (https://www.topbrass-inc.com/collections/brass). The ex-military stuff is guaranteed to be once-fired, and is inspected, cleaned, resized, trimmed and has primer crimp rings removed. Edgar Brothers’ list of its brands no longer contains this one, though. It would have been boorish to put it mildly to be other than grateful for the gift but, I did warn that putting previously fired arsenal cases through my 223 and 308 match rifles is entirely counter to my practices, religion even. So, the two packs sat in view on a shelf that holding other, rather higher-grade cases and mocking me every time I had a loading session. ……… for a LONG time!

Then, when I was loading and shooting large numbers of Lapua 223 Rem cases on a near weekly basis for VarGet and H4895 alternatives, results written up in the ‘Reach-Out’ series, I decided to indulge my curiosity over the impact of brass type/quality on short-range precision, not to mention appease my conscience and give this ‘223’ ‘Top Brass’ a go. I had just finished testing Lovex S062 and got a couple of nice, tight groups with it under the 77gn SMK in Lapua brass, so loaded up another 30 rounds with what had apparently been the best charge-weight of this powder, now in the military cases and, as with the Lapua originals, shot them off the bench in my heavy Savage PTA-based F-Class rifle.

But before looking at results, let’s first look at the ‘Top Brass’ cases and compare them to high-grade commercial equivalents. As promised by the company, they are all NATO standard 5.56 as shown by the little circled cross stamped on the case-head. Also, as described, they were of mixed origin, but mostly ‘LC’, from the US Lake City Army Ammunition Plant (LCAAP) in Independence, Missouri. Of the 50, 43 came from this source, the others made up of five TAA (Taiwanese), and one each from WCC (Winchester) and IVI (Canadian). The Lake City cases had a 10-year date-stamp range (02-12), but most were 09. (I’ve been told the year-stamp doesn’t guarantee they were made that year or from a single production run as the LCAAP periodically produces huge runs of brass and stores them until drawn down for priming and loading, headstamps applied at that point).

Physically, with one badly dented exception, Top Brass’ examination, cleaning, sizing, trimming work was good and the swaged-in primer crimp rings had been cleanly and expertly removed. The case comparator gave very consistent base to shoulder position readings across a good size sample. So, the Top Brass cases were primed, loaded and fired pretty well as received.

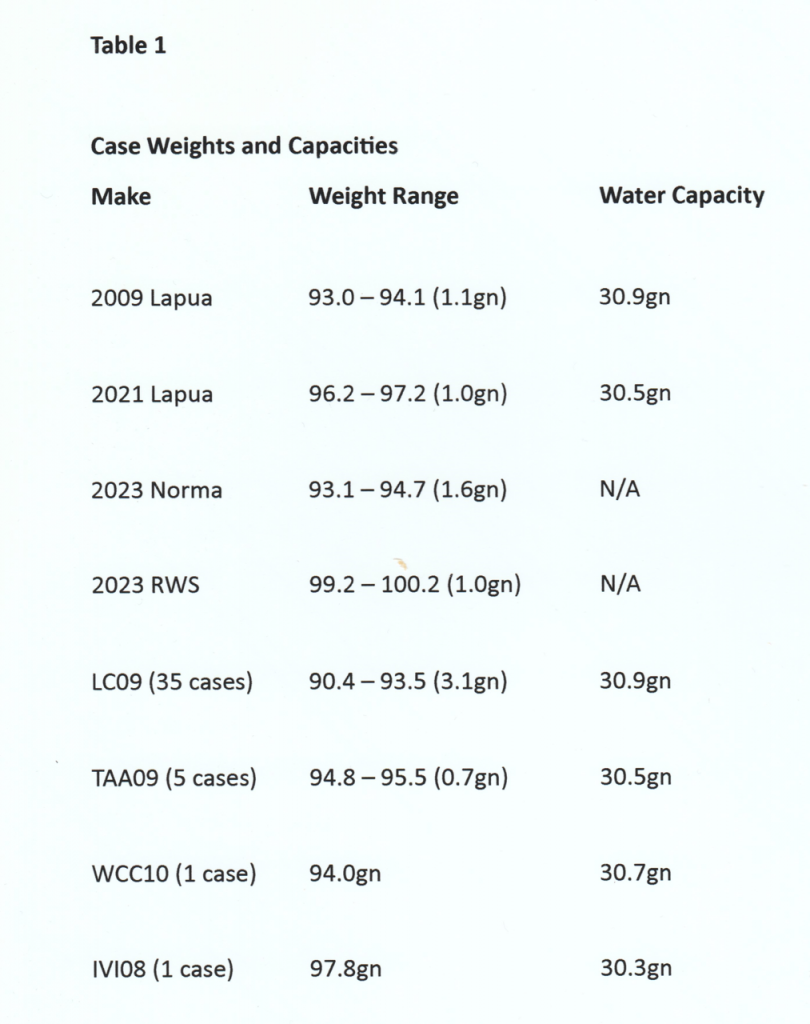

The table provides the salient details of the four military grade cases alongside those of best European commercial 223s. In terms of weight and (fireformed) water capacity, LC09 matches early (‘Gold Box’) Lapua ‘Match 223’ as the lowest weight / highest internal capacity. TAA and WCC examples are close to (‘Blue Box’) Lapua bought three years ago and the sole IVI case has the lowest water capacity of the bunch. However, I have yet to fire any of my recent manufacture Norma and RWS 223 brass and expect them to respectively represent the highest and lowest capacity models of my collection based on their unprimed weights.

Rubbish Brass?

I rather provocatively used those words in the feature title, but are these once-fired cases ’rubbish’? We can only answer that by returning to the question of standards, that is what the rifle, barrel and ‘scope are capable of in precision terms, also what the user expects. My acquaintance’s gamekeeper brother would surely find them more than adequate for fox control. On the other hand, 6PPC short-range benchrest competitors aren’t going to switch from new Lapua .220 Russian cases as their starting point to mixed once-fired military 7.62X39mm when creating 6PPC match brass.

It is the Top Brass LC cases’ previously fired and multiple production lots features that produce many reservations about this source. Although in externally good condition after Top Brass’ preparation, and lacking the beat-up case-heads of those fired in the police rifles, they were still made in multiple production lots and fired in many individual rifles, some undoubtedly with slack, maybe even out of spec, chambers. So, cases will have seen varying degrees of stretching, swelling, and subsequent sizing / trimming workloads in being reprocessed, a poor start for any precision application, perhaps affecting lifespans too. Being from different makes and lots, there may be variations in neck thickness values affecting neck-tension and other such differences in addition to their capacities.

In the USA, Lake City 5.56 brass is not regarded as ‘rubbish’, some serious F/TR 223 Rem competitors using it in their practice ammunition, even short to mid-range matches. However, that is starting with new, unfired examples which are sometimes available through the larger American component suppliers. Midway-USA currently (August ’24) has such cases in a sale offer at $64.99 for a 250-case box, 26 cents each. (That’s 20-pence in our money, and even with VAT added, when could you last buy new rifle brass here for £25 per 100?).

Standard procedure for precision shooting is to buy a large quantity (500 or 1,000), then weigh and measure them, batching up consistent examples. A bit more case-preparation subsequently won’t go amiss either. The result can be strong, high-capacity and very respectable cases, if not as good as say, Lapua, but many users won’t care at that price. (This is however trading personal time in batching / preparation against monetary outlay, high grade commercial match brass being almost ready to load and use). The US Army Marksmanship Unit has also used new LC 5.56 cases on occasions for its handloaded match ammunition but, note the High-Power XTC competition uses larger-ring targets (1-MOA ‘X’; 2-MOA ‘10’) than F-Class. USAMU comments on how strong LC 5.56 case-heads are compared to some commercial 223 makes. Of course, most American purchasers won’t fall into the precision shooting bracket and will use such cases – as received – in AR-15s or mass-produced bolt-action sporters.

Three of the four case makes in the Top Brass mix have either the same or higher water capacities than those of my two primary Lapua batches, and the fourth (IVI) is only slightly reduced at 30.3gn counter to the common view that all arsenal cases are heavier / lower capacity than their 223 or 308 commercial equivalents. (7.62mm military cases do normally have thicker walls / lower capacity than commercial 308 Win and thereby do need reduced charges but, the situation varies considerably across 5.56, only some makes exhibiting this trait. If unsure about this, it is prudent to run lower charges with 5.56 cases than the ‘book maximum’ shown in reloading manuals whose pressure-tests use 223 Starline, R-P, Winchester etc commercial products).

Why Cases Matter

How much difference do those capacity variations make in this cartridge and components combination? QuickLOAD calculates a difference of c. 2,700 psi in peak chamber pressure between the roomiest (30.9gn water LC) and smallest (30.3gn IVI) with this S062 charge weight, the light / high-capacity case having the lower pressure. That will be on top of the cartridge’s inherent shot to shot chamber-pressure range, which is likely to be significant given the 223’s propensity to produce large MV ES values. Throw in possible neck thickness and even brass alloy differences which affect neck tension levels and other behaviours under firing pressures and, you can see why mixing makes in an ammo batch is a bad idea – and that’s before we get into basic manufacturing precision and case to case consistency which we can expect to be lower in cheaper and arsenal-grade products.

This is where we encounter the issue of case wall consistency. Traditionally, American cases from the large manufacturers were less consistent than the best European commercial equivalents. At one time, American commercial brass would regularly see five thou’ variations in thickness values around the case body and the American Palma shooter, gunsmith, and experimenter Creighton Audette found some with up to 12 thou’. As long ago as the 1930s, the US Frankford Arsenal found that increasing the number of brass drawing stages during manufacture improved wall thickness consistency and the results shot better. (Lapua undertakes a very large series of such draws allied to several intermediate annealing steps in its manufacturing process, which coupled to the company’s engineering expertise and vast experience in this field, is why its case bodies are of such consistent radial thickness alongside finely graduated degrees of metal hardness from the base to shoulders). Note, I’m not referring here to thickness at different points along the case-body as we move from the head to shoulder, rather variations at any given place between those points as the case is rotated and measured around its circumference.

Creighton Audette did a lot of work on this 40 odd years ago and proved experimentally that inconsistent case wall thickness directly affects shot dispersion patterns / group size. He invented a tool (later made and sold as the NECO Gauge – https://www.neconos.com/case-gauge-info/) which, as well as being a case/bullet runout gauge, can be used to measure wall thickness variations as the case is rotated on V-blocks. This allowed him to mark-up cases indicating the thin/weak body-side and index them at different positions in the rifle chamber. As the thin side stretches more under combustion pressure in the chamber, the case-body bends, and the case-head face is forced out of square against the bolt.

In two-lug actions with the lugs at the six and twelve o’clock positions when locked, Audette found there is little effect on the group if the cartridge is always chambered with the thin-wall side positioned at those points, but incurs a growing degree of dispersion as it moves round, topping out at the least supported three or nine o’clock positions. (This is one reason why Swing / Paramount / RPA four-lug rifles became dominant in UK ‘Target Rifle’ back in the days of mediocre arsenal 7.62mm ammunition, whilst contemporary top-notch twin lug benchrest actions managed to produce small consistent groups employing cartridges with much higher quality, fully ‘prepped’ brass). Audette wrote his findings up in the September 1986 issue of Precision Shooting magazine. (http://freepdfhosting.com/bd7fee7eed.pdf starting on page 13 of the original PS article print).

Both Frankford Arsenal and Audette concluded that somewhere around 0.003-inch variance represents the point where the case starts to affect group size and the dispersion pattern. Audette also hypothesized that short, fat, sharp-shouldered cases might mitigate these adverse effects through bending less in the chamber even when they have some wall inconsistency. (It could also be that case manufacturers find it easier to make low wall-variation cases in this form.) In either event, this may be another reason why this case-form is now regarded as an essential element in high-precision cartridges. It certainly seems intuitively right that long, steeply tapered cases like 300 H&H Magnum will distort more in the rifle chamber if they suffer from such manufacturing faults than the shorter 308 Win, never mind the BRs or PPC. Walls aside, manufacturers have been known to produce cases whose heads aren’t 100% square to the axis. Not good! Some military-grade 7.62mm ammunition issued to ‘TR’ competitors was said to suffer from this defect and again, the four-lug Swing rifle ‘family’ gave superior results.

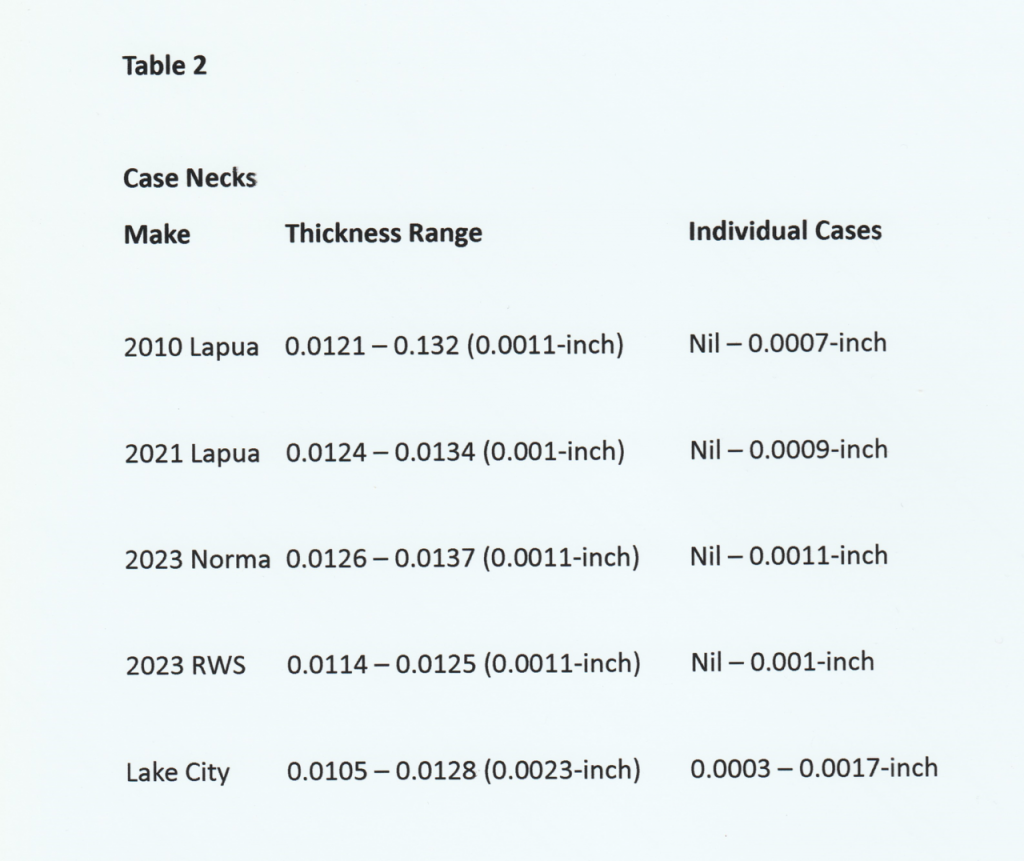

Whilst few are going to laboriously look for case-wall thickness irregularities, it’s not too hard to do so for case-necks. This requires a small ‘tube’ micrometer capable of measuring to 0.0001”, that is one tenth of a thousandth of an inch, or mighty small. (If you’re contemplating neck-turning, you need such a mike). I have a little Starrett mounted on a heavy steel base set up just for this job that I bought from Sinclair International years ago, but there are cheaper models around. The idea is to rotate the case around its anvil, (which has a ball on the end) and take three or four readings at different points to see how much variance there is in neck thickness. If there’s a lot in any individual case, the seated bullet might not be concentric in relation to the bore and, as with every other case feature, case to case differences may produce inconsistent results. That’s why precision shooters often do a light neck turn – to ensure every case has near identical thickness around the neck, also so that every case in the ammunition box has the same thickness. Look at Table 2 for ‘Top Brass’ Lake City cases vs Lapua, Norma and RWS and there are larger variations evident in the arsenal brass.

Three readings were taken around the neck on each case, so a total of 60 for the twenty Lake City examples. (Up to 60 cases were so measured for each of the Lapua, Norma, RWS lots). ‘Thickness Range’ in the table shows the smallest and largest overall readings from the totals, that is of 60 readings to use the Lake City example again, whilst ‘Individual Cases’ narrows that to the differences recorded across the three readings in individual cases. Around half of the latter have variations around their necks of a thou’ or more, the largest approaching two thou’. By comparison, the worst example in the Norma sample is a fraction over one thou’ and that was exceptional with 60% having nil to 0.0003” variance. Lapua 223 brass usually has half to three-quarters within nil to 0.0005” (half-thou’), the remainder under a thou’.

Those ‘Top Brass’ cases are by no means the worst I’ve encountered, for instance a commercial make of 6.5mm Grendel brass being poorer across the board with a single worst example from 100 pieces that miked at almost 3 thou’ difference between thick and thin sides. (When you find neck thickness variations of this magnitude, there is a high probability of them being carried down into the case-body walls and becoming still larger).

Tests and Groups

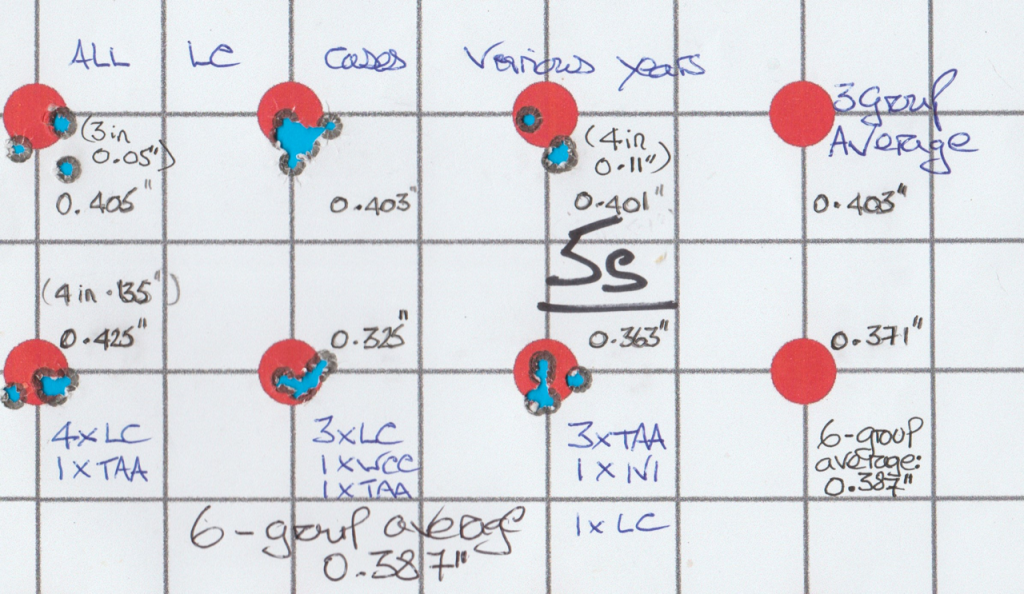

Moving on from theory to a modest range test, I loaded up 6 by five-round batches with ‘Top Brass’ cases – three using Lake City examples only, the others with a mix of LC cases and the seven examples from other makes spread around to inject capacity and possibly other variabilities. There were therefore two tests in the exercise. How much difference did mixed arsenal brass make when compared to a single make? Secondly, how did the arsenal brass perform overall against Lapua?

Brass aside, all cartridges were as per the original ‘Reach-Out’ powder test load: PMC SRM primer, 77gn Sierra MatchKing bullet seated to a common CBTO comparator reading value some 20-thou’ off the lands (at 2.400-inch COAL in this very long-freebore chamber) and 24.6gn S062, charges individually weighed and adjusted to be consistent. Note that this charge-weight exceeds that of the US Shooters World 223 Rem maximum for its ‘Precision’ grade (S062 under a different name) and this bullet in the low-freebore SAAMI chamber but, is well under the same company’s maximum in the longer freebore 5.56mm chambered pressure barrel.

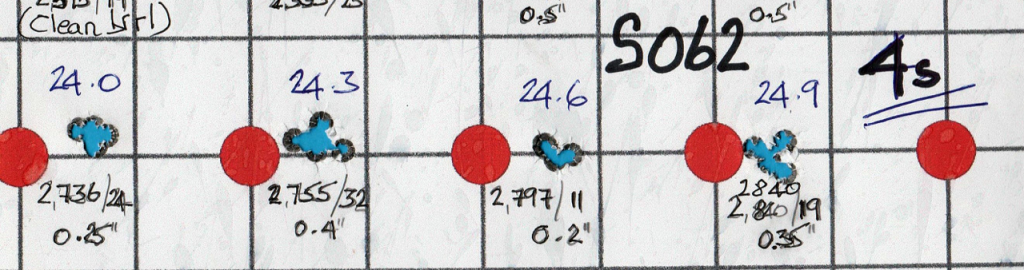

The original Lapua brass S062 test loads provide the benchmark for judging the ‘Top Brass’ equivalents, so I’ve reproduced part of the target scan (above) originally published in Reach-Out part 6 https://www.targetshooter.co.uk/?p=3811 The original test involved nine four-round test batches covering 22.4 to 24.9gn charge weights. The first five charges’ groups on the target’s top line gave variable results, but MV consistency and group size improved for the four highest charges shot on the second line, and that is what is reproduced here – four groups with a range of 0.23 to 0.415-inches.

The other target scan (above) is that of the ‘Top Brass’ loads’ groups, the upper line Lake City, the lower with mixed makes. Looking at the 3-group averages on the right, the ‘rough as a bear’s rear end’ mix produced the smaller result, by some 8%. Would you believe it? This wasn’t what was supposed to happen – but, this isn’t the first, or I’m sure the last time, that handloading and ammunition testing has produced ‘perverse’ results for me! There is a likely reason for this outcome – those random factors that affect individual groups. If I were to show these groups to Bryan Litz of Applied Ballistics LLC, who has experimented with and written extensively about inherent group-size variations, I have no doubt his response would be on the lines of: ‘Repeat the test several times to obtain a valid basis for comparisons’.

A few comments on these groups. The all-Lake City trio produced an astonishingly consistent size to within 0.004-inch (four thou’). This must be a statistical freak, especially as they display different patterns. Load and shoot them half a dozen times and we would almost certainly see a considerable range. Before anyone asks, they are all five-shot groups, that on the top left having three shots in the high hole miking a tiny 0.05-inch. Two other groups (top right and bottom line left) have four shots in an impressively small dispersion plus a single outlier opening the overall group to around 0.4-inch. This tells you something about the limitations of making decisions based on single three, even four, round test groups. Take that top left example. If (a big if, I know), the three shots in that single hole had been shot before the other two and I had limited the test to 3-shot groups as many shooters do, I’d have come away from the range with a group that suggested 223 Rem with reused arsenal brass was capable of producing Benchrest competition ‘screamer group’ levels of precision!

The four plus one pair had the 4s measuring 0.11 and 0.135-inch suggesting that there is a promise of good results trying to get out, but spoilt by a single outlier. What might be behind these patterns? Given that I was testing recycled arsenal brass, it’s very tempting to assume a single case is at fault. It must be that TAA case in the bottom left quintet that opened a 0.135-inch group up to 0.425, you might think. It is such a convenient solution it tempted me to think this way, but the flier wasn’t produced by the round loaded in that case! Brass variation remains a possibility though – a rogue asymmetric case as described by Creighton Audette, sometimes called ‘a banana case’ from its behaviour under firing pressure, or maybe the other variations injected by these cases coming from different production lots and previously fired in multiple rifles and chambers – or then again, it was just as likely to be from something entirely unrelated to these factors.

Slam Dunk?

Moving onto the main comparison, that against the same components loaded into Lapua brass, it seems there is an obvious, large deterioration in precision here, where the only changed variable is the brass. The original Reach-Out 24.6gn S062 test group measured 0.232-inch centre to centre. No ‘Top Brass’ group came anywhere close, the nearest being 0.325, and the six-group average was 0.387, increases of 40 and 67% respectively. A ‘slam dunk’ result then to use an Americanism, or ‘open and shut case’ as we’d say. But, is it really?

It’s not, as the nature of shot dispersion / group sizes is such that you cannot cherry pick a single small group and take it as representative of what all shots loaded with that combination will do. One-off groups can be wildly out of the average (in either direction) and in practical terms unrepeatable. I had an extreme example years ago when I shot a Savage 12 LRPV in 204 Ruger in 100 yards benchrest ‘Factory Rifle’ class. During load development, I got a five-shot group in the low ‘ones’. It used Hornady VMax varmint bullets, no handmade super-grade projectile, and I can’t remember the powder. ‘Have I cracked it?’ I asked myself. It seemed too good to be true – and it was! My next range visit saw several groups fired with the same combination to confirm the result. Not only did none replicate the original, but the smallest was getting on for three times as large! The range visit after that saw the same combination tried with charges bracketing the original weight in 0.1gn steps. No better! That one-off was my smallest group with the rifle in a couple of thousand rounds, but completely unrepresentative and unrepeatable. (The best I achieved in competition was 0.207-inch with an entirely different combination and, that was an atypically small group within the overall picture).

I’d been impressed by S062’s consistent performance from 24.0gn and up across a 0.9gn charge range in my original Reach-Out test. To get a reasonable base value to compare the ‘Top Brass’ loads against, I averaged those four groups giving me a new Lapua group size of 0.302-inch. But we’re not done yet as the original test groups were four-shots and the ‘Top Brass’ equivalents were fives. Bryan Litz gives a statistically based table of weightings to ‘convert’ group sizes to their different number of shots equivalents (Modern Advancements in Long Range Shooting Volume II), in this case by multiplying the original figure by 1.1, giving us 0.332-inch which isn’t too far from the smallest ‘Top Brass’ result. The six-group ‘Top Brass’ average of 0.387-inch is therefore 0.055-inch or c. 17% larger than with the Lapua case rounds. Lies! Damned lies! And Statistics! is the traditional reaction to such number-mangling and you might disagree with the methodology. I feel comfortable with it, especially as some five-round groups were later fired with the Lapua cased 24.6gn load and returned values not much under the third-inch mark my ‘adjustments’ had come up with.

So, is my conclusion that apparently ‘rubbish brass’ produces not that much worse results than top-grade Finnish products when shot in a heavy barrel match-specification rifle? On one level yes and, for many short-distance ‘plinkers’ or field shooters such cases may well be good enough. The 80-20% ‘rule’ once beloved of management consultants likely applies here. (Put crudely, it says 80% of likely eventual results / improvements come from 20% of the expenditure in time and money spent in an improvement scheme, but it takes the other 80% of the full outlay to achieve the remaining 20% of possible benefit.) The other factor in play here is that the original Reach-Out test showed that this powder / bullet / charge weight combination performs well in my rifle, and that case quality/consistency likely determines a relatively minor part of that result.

I’d still say buy Lapua, Norma or suchlike as you should obtain the best made products you can. If nothing else, they’ll give you more firings before scrapping and reduce the likelihood of unexplained fliers. I should add that true precision shooting aficionados go the whole hog and seek to achieve that final 20%. Top benchrest competition shooters obtain consistently small groups by doing everything possible to minimise the variables that influence group-size dispersion (in rifles, ammunition components and preparation, and shooting technique) and thereby successfully negate what Bryan Litz says below. As always, it is a case of ‘horses for courses’ and, using the best possible case prepared to the nth degree is justified, even vital in high-level precision shooting. (See what Vince Bottomley says about this in a recent TS review of some superb ARC Ballistics handloading tools – https://www.targetshooter.co.uk/?p=3921. Vince writes here in the context of short-range benchrest, but his words apply as much to high-level F-Class and to extreme precision long-distance field shooting).

Moreover, to agree with that oft-used put-down (Lies! Damned Lies! ….), averages plainly don’t tell you everything. Compare the group shapes from the two types of brass. Those from the Lapua cased rounds are much ‘nicer’ without a single flier separate from the main body. Mid and long-range competition and field shooters are rightly obsessed with shot-consistency, especially in ‘elevations’, the objective being to have every bullet land along an imaginary ‘waterline’, a horizontal line through the middle of the aiming mark. You can read the wind, but unpredictable high or low shots make hit-probability a lottery, especially as the distance to the target or quarry increases. On that note, these tests were conducted at 100 yards – OK for the ‘plinker’ or some ‘foxers’ but I’d wager that moving to 300 yards would see the performance disparity between the two lots grow substantially and, at 600 yards (which this 223 Rem combination is easily capable of), it really will be a ’slam dunk’ decision in favour of the higher quality brass.

Addendum: Bryan Litz, Applied Ballistics

Bryan and his company have experimented extensively covering many subjects in handloading and internal/external ballistics. In the course of this work, AB team members have shot literally thousands of groups. From this experience, including an experiment involving no fewer than 45 five-round groups with a single load combination shot under controlled conditions, he has written about the nature of groups and their size ranges in two of his books – Modern Advancements in Long Range Shooting Volumes II and III demonstrating that just as with MVs, groups display considerable disparities even with a single load in one rifle, in fact produce a classic ‘bell curve’ statistical dispersion when multiple group measurements in a series are graphed. I intended to summarise the key points on this subject in the two books to justify my group size ‘adjustments’, but fortuitously Bryan recently did this himself on his Facebook page (https://www.facebook.com/BryanLitzBallistics) which I have shamelessly plagiarised.

“Many shooters seem to expect a gun to shoot basically the same group size all the time, but that’s simply not how it works.

What we’ve seen over 100’s of 5-shot groups from 223 thru 375 is that the standard deviation of 5-shot groups is about 30% of the average. Statistics tells us that 67% of groups will be between +/-1 SD of the average, and 95% of groups will be within +/-2 SD’s of the average.

So for example, if your long term group average is 0.5 MOA, then 67% of your groups will be between 0.35 and 0.65 MOA. Likewise, 95% (19/20) groups will be between 0.2 and 0.8 MOA. Anything in that range is completely normal for a 0.5 MOA average. This is the nature of dispersion.

For this reason, it actually takes a lot of 5-shot groups to accurately characterize the true average precision. We consider five 5-shot groups decent but, sometimes it takes ten 5-shot groups to resolve a genuine precision difference. Remember this next time you’re doing load development and call one load ‘better’ than another because it shot a 0.4 vs. 0.5 MOA group. Those single samples are more likely to be the same than different”.

For more information on Applied Ballistics, its services, products and publications (printed and online): https://appliedballisticsllc.com and https://thescienceofaccuracy.com