If you’ve ever been fortunate enough to attend the NRA’s Imperial Meeting, staged annually at the famous Bisley shooting complex, you may have come across the McQueen competition – you can enter on the day without the need for a rifle or ammunition.

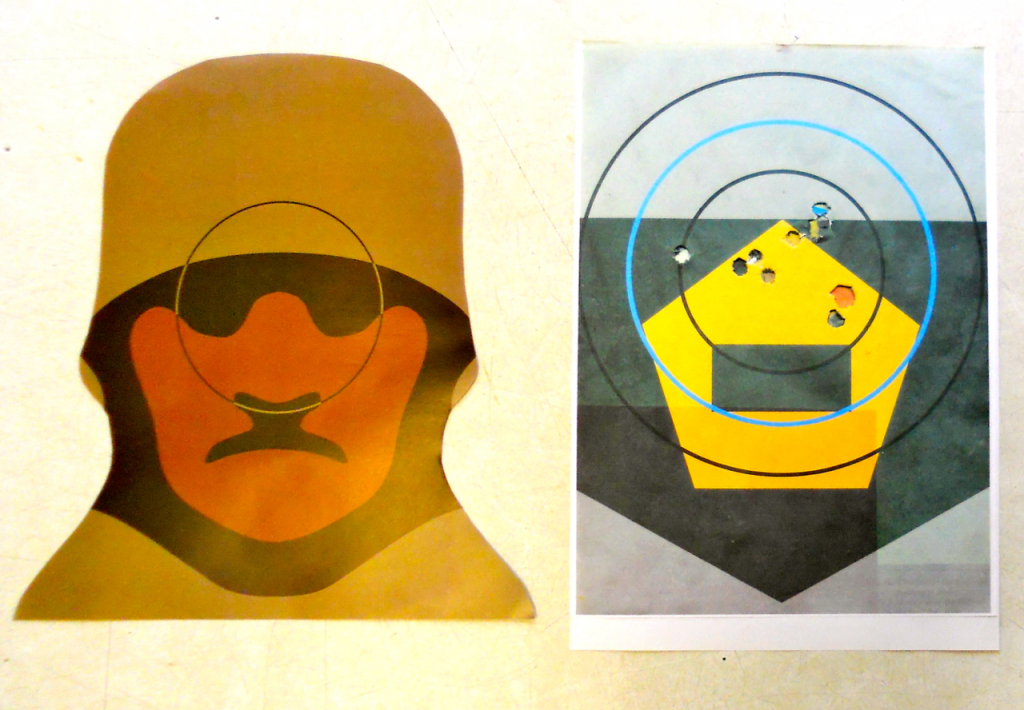

The format of the McQueen competition is quite simple. At a distance of 200 (or 300) yards from the firing point stands a ‘wall’. In the wall are a number of randomly placed rectangular holes. The target is a two-dimensional life-size ‘head’ mounted on a long stick. Closer inspection of the head reveals that it bears a scant resemblance to a WW1 German soldier, resplendent in grey tunic and helmet. On the temple area of the target is inscribed a four-inch diameter circle and five points are awarded for a hit in this circle and four points anywhere else on the target.

Ten exposures of the target, each of three seconds duration, are given to the shooter, with an away time of 5 to 20 seconds. The ‘head’ appears randomly at any of the window openings in the wall – safely manipulated by the butt crew below the wall. The ‘wall’ is a flimsy structure of timber and canvas (we use Corex) to eliminate the risk of ricochets.

The origin of the McQueen competition is interesting. Is it just a fun comp? Why the Hun’s head target? Who devised it? Could it have been a one-time sniper training aid?

Of all the military roles, that of the sniper continues to fascinate the civilian shooter, who similarly has an obsession with extreme rifle accuracy at long-ranges. The role of the sniper in warfare has probably existed almost as long as the rifle itself, though the term ‘sniper’ has its origins in the sport of shooting snipe in India in the nineteenth century. There are well documented accounts of extreme long-range kills perpetrated by the Boers on the British Army during the South African campaigns. The Boers were but poor farmers and ammunition was a luxury item. Their rifles were primitive by modern standards but it was essential that every round was made to count when hunting game for the pot. By using their hunting skills against the vastly superior British Army, they almost upset the mighty British Empire and in doing so unwittingly invented what we recognise today as guerrilla warfare.

About the same time as we were rampaging in South Africa, America had its own internal problems and there are many notable sniping incidents recorded by both sides in the Civil War. (Read about Hiram Berdan’s Sharpshooter regiment). Strangely though, the British Army at this time considered sniping to be an un-sportsmanlike way of fighting the enemy and were content to engage their foe – be it black or white man – at more respectable distances with the Martini Henry and Snider Enfield.

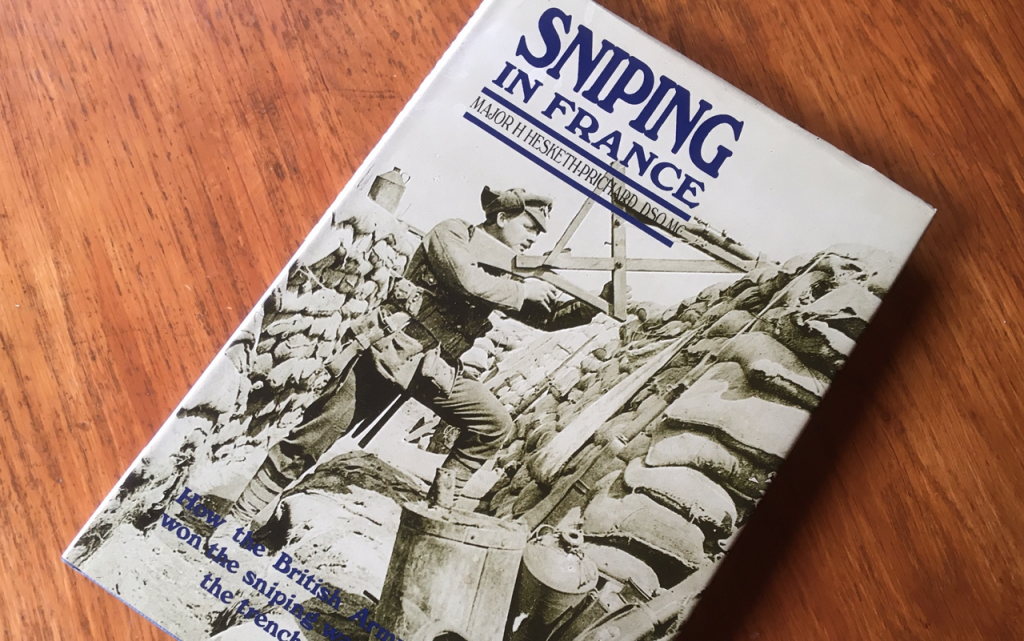

However, following the devastating and demoralising carnage caused by German snipers in the first World War the British Army did recognise the role of the sniper and I came upon a rather interesting book, simply entitled ‘Sniping in France’, which documents the eventual adoption of sniping by the British Army in WW1.

The British Army issued ‘selected’ versions of the Enfield P14 (.303 version of the Model of 1917) for so-called sniping. Although the rear ‘peep’ sight was a great improvement over the standard issue Mk 3 Short Magazine Lee Enfield (SMLE), it was no match for the German sniper, whose Gewher 98 rifles were now equipped with telescopic-sights – some 20,000 donated via the German hunting fraternity from their cherished rifles!

In Britain at the beginning of the 20th century, hunting with the fullbore rifle was rather limited, though there were a few Scottish deer-stalkers and of course the odd big-game hunter. One of the latter was Major Hesketh-Pritchard who, as well as being a knowledgeable exponent with telescopic-sighted rifles, also had some first-hand experience of trench warfare.

The Major soon began to notice the moral-sapping effect of the German snipers on his troops: “The hardiest soldier turned sick when he saw the effect of the pointed German bullet, which was apt to key-hole so that the little hole in the forehead where it entered often became a huge tear the size of a man’s fist on the other side of the stricken man’s head”.

At that time, most of the German sniping was carried out by shooting through a ‘loophole’ – usually a small elongated hole cut in a thick steel plate, which in turn was mounted on top of the trench and heavily protected by sand-bags and earth. This effectively made the sniper immune from return-fire, for the iron-sighted P14s could not hope to reliably hit the tiny loophole or pierce the steel-plate. Immune that is until Hesketh-Pritchard began carrying out penetration tests on steel plate with his hunting rifles. He quickly found that the formidable .333 Jeffreys*, a popular African big-game round capable of pushing a 250 grain bullet at around 2500 fps, would scythe through the steel plates ‘like butter’ and so he took one, equipped with a telescopic sight, to the front.

One can only imagine the look on the faces of the enemy when that first 333 Jeffreys round ripped through their ‘impenetrable’ loopholes – now about as protective as wet cardboard! But Major Hesketh-Pritchard was only just beginning. As well as copying the Germans and rounding-up as many civilian telescopic-sights as he could, he also began to teach would-be snipers not just to shoot but how to set-up and adjust their new sights. He was quick to analyse sniping as not just “hitting your mark” but also “finding and defining the mark” and he thus developed the two-man observer/shooter sniper team – a technique still favored by the military.

Eventually, the results of the Major’s endeavours began to filter through to the‘top-brass’ and the first British Army ‘field’ sniper-school was established at the village of Bethune in France. Always on the look-out for talented shooters, the Major soon enlisted the help of a young soldier by the name of Gray, who appeared to be a little more knowledgeable than the average when it came to long-range shooting. Again, if the reader is ever fortunate enough to visit Bisley Ranges, you may see the name of Lieutenant W.Gray in the NRA pavilion, together with all the other previous winners of the coveted Queen’s Prize.

Hesketh-Pritchard recalls that, as a school training aid, brick walls, with several random holes were devised. The would-be snipers practiced by shooting at a life-size papier-mache Hun’s head mounted on a stick, which would randomly appear in any of the holes for a two to four second exposure – from a distance of two-hundred yards. Sound familiar?

Readers may like to think that modern sniping has taken on a different role in the intervening 90 years but Major Hesketh-Pritchard’s methods soon made the steel-plate loopholes too dangerous to use and the art of concealment became the new game. He did not of course have the ghillie-suit as we know it but he developed the sniper’s ‘robe’ and relates the tale of a sniper crawling into no-man’s land under cover of darkness and concealing himself inside the rotting carcass of a dead horse before making his shot in day-light, remaining concealed until darkness fell once again and then returning to his trench! It was a steep learning-curve in those days, even to the realisation that rifles could become shot-out with too much practice!

If you don’t think the McQueen would make a good modern day sniper training exercise, you are probably right but, as a club competition, it’s great fun and very popular at my home range of Diggle. We shoot 2 sighters and then 10 shots to count at 200 and 300 yards. The ‘target’ appears randomly for just three seconds at any of the ten or so ‘windows’ – swing the cross-hairs onto the four-inch circle, hold your breath and squeeze off the shot! Do that ten times and a perfect 50 is yours. Easy! A coveted patch is awarded to those who manage it.

But why, I wondered, is it called the McQueen? (Note – no ‘s’) There exists in Galashields, Scotland, the famous target printing firm of that name. Surely the two must be associated. The firm was founded in 1840 as a simple printing works but in 1890, John Stirling McQueen, the founder’s son, was asked by the sergeant-at-arms of the local volunteer force, to print some ‘penetrable’ targets for a forthcoming shooting competition. Prior to that, all shooting practice was done on steel plates, which were painted in whitewash so that the shot-impact could easily be seen. The target was then simply white-washed ready for the next firer (which is incidentally how the term ‘whitewash’ entered our sporting vocabulary).

In the early days of the NRA, the Association was more closely linked with the Military than it is today. Firing practices were the same and civilians competed alongside the military as they still do in the USA. When target-shooting resumed after WW1 there was a call for a sniping competition by the returning troops and the NRA asked McQueen (by now printing most of the paper targets in use) if they would print some appropriate Hun’s Head targets. Not only did McQueen supply the fig.14 targets, they offered to sponsor the competition – with a magnificent silver trophy.

Two of our Diggle members, John Coleman and Rob Hunter are McQueen exponents and both have won the coveted McQueen Silver Eagle trophy, awarded to the winner of the McQueen competition staged at the annual Bisley Imperial Meeting.

There are monthly McQueen shoots at Diggle Ranges cumulating in the fiercely contested PSSA McQueen Championship (see calendar). Any decent centrefire rifle with a scope and bi-pod is suitable and many cartridges from the 308Win down are used but the 6.5 is probably the most popular calibre. A zoom scope is preferred as not more than twelve power can be used at 200 yards – to view the whole wall – increasing to about 18 power at 300 yards. A bi-pod is essential but rear support under the butt is not permitted. Although most shooters will use a repeater, a magazine is not necessary as there is adequate time to single-load. You will need to bring 24 rounds – plus a couple ‘just in case…’

Anyone who would like to obtain a copy of Major Hesketh-Pritchard’s splendid book is invited to contact the publisher, Leo Cooper, Pen & Sword Books Ltd. 47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire. S70 2BR Tel 01226 734555. Price plus P&P. All cards accepted. Genuine Hun’s head targets (order as fig. 14) can still be obtained from the original McQueen print works at Galashields, Scotland.

Though hurry – rampant political correctness has forced the NRA to ditch the genuine Hun’s head and replace it with a new version which is just a mess of brown, black and grey blocks! Is Major Hesketh-Pritchard turning in his grave?

* The 333 Jeffrey. This is a necked-down version of the more popular 404 Jeffrey utilising a rimless bottleneck case. It was introduced in 1908 by W J Jeffrey & Co and is capable of driving a 250 grain bullet at 2500 fps. – giving an m/e of about 3480ft/lbs – about the same as a modern 338 Winchester Magnum.